This article which I wrote recently has just been published in the May 2023 edition of The South Australian Genealogist.

This is the article.

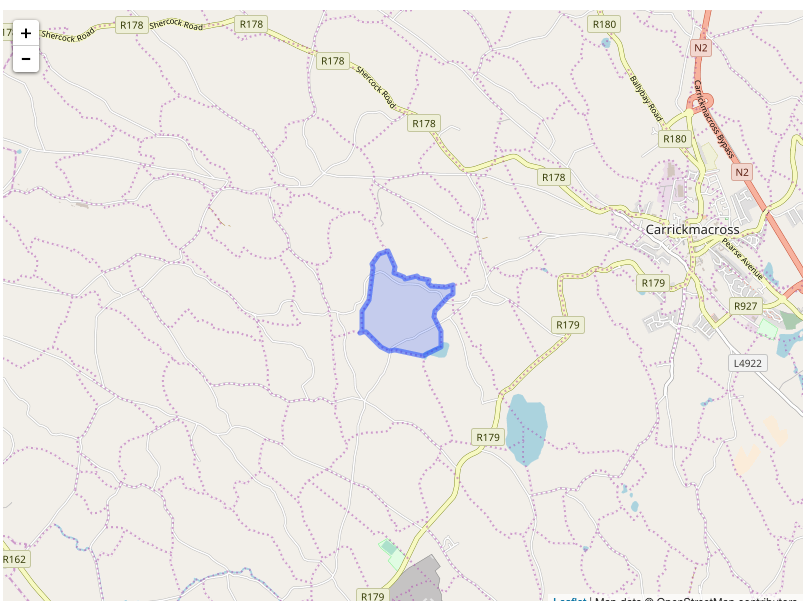

‘Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church, Dawson’ painted by Bruce Swan. Image courtesy of Steve Swan.

There is an evocative painting by South Australian landscape artist Bruce Swann, Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Dawson of a once beautiful small church standing alone in a dry landscape on a hot summer’s day. It is a forlorn symbol of the lost dreams of hard-working pioneers.

This church has a significant place in the history of my maternal ancestors, the Dempsey family. My great grandparents helped to build the church. Until I began researching my family history, I had never heard of Dawson or Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church. “Our Lady of Mount Carmel” is the name given to Mary in her role as patroness of the Carmelite religious order. The Carmelite order was founded on Mount Carmel in the 12th century. Mount Carmel is a coastal mountain range in northern Israel. Carmelite tradition has it that a community of Jewish hermits had lived at the site since the time of the prophet Elijah (900 BCE). Elijah is revered as the spiritual Father of the Order. Shortly after the Order was created a Carmelite monastery was founded at the site dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Another Bruce Swan painting of Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church in Dawson, from a slightly different angle, was commissioned by the people of South Australia and presented to Pope John Paul II on his 1986 visit to Adelaide. It is now part of the Vatican collection. The Church is listed on South Australia’s Heritage Register with the following citation:

Dawson's Catholic Church, Our Lady of Mount Carmel, built in 1886 is of significance because it evocatively illustrates the pattern of settlement associated with the expansion of the agricultural frontier that occurred as a result of land reform from the mid 1870s. With extreme optimism, small farming communities were established far north of Goyder's Line of Rainfall and hamlets developed. In Dawson, this fine church was built, anticipating a thriving community. The architect for the building, Father John Norton is of significance as a competent architect turned priest and was responsible for several buildings in the region. Of course, the town of Dawson and its envisaged wheat farming community did not occur, beaten by years of drought in country best described as marginal. Dawson's Church evokes all of this history and stands in this barren landscape as a monument to the failure of the later Strangways resumptions.

The 1880s saw the construction of Methodist and Anglican churches as well as the Catholic church. The Dawson Hotel was built in 1883. A public school opened in 1885 after several years of agitation by local residents. Local government came to the area in 1888 with the District Council of Coglin which met alternately between Dawson and Lancelot. In its heyday, Dawson had multiple stores, an Institute, an agricultural bureau, and a blacksmith.

My great grandparents were among the unfortunate early settlers who tried farming outside Goyder’s Line of Rainfall. George Goyder was South Australia’s first Surveyor General who determined that land beyond a certain line was not suitable for agriculture as it lacked reliable rainfall. The government of the day ignored his warnings, and knowingly sold land to unsuspecting settlers. The countryside around Dawson has returned to its native vegetation, mainly salt bush and mallee scrub. Farmers run a few sheep. There is little trace left of the community who once lived there.

My grandfather, Patrick Joseph Dempsey was born on the family farm near Dawson on 17 July 1887, the second child of my great grandparents Andrew Felix Dempsey and Mary Ann Naughton. Their first child, a daughter named Mary Bridget, was born on 22 March 1886. She lived for only 11 days and was buried in the Dawson cemetery. In the photographs I have seen of my great grandmother as an old lady, she looks rather stern. I tried to imagine her feelings as a young woman, coping with the grief of losing her first child soon after birth. Altogether Mary Ann had eight children born near Dawson between 1886 and 1901.

Mary Ann Dempsey (nee Naughton) with her granddaughters Patricia and Mary Dempsey. My mother Mary Dempsey is the baby on her lap. 1915.

A few years ago I went on an ancestral journey of discovery in South Australia, visiting the places where my ancestors had once lived. Dawson was the last stop. We turned off the Barrier Highway north of Peterborough on to a rough dirt road. It did not look promising. There had been heavy rain that winter and we were nervous about getting bogged, an experience we had already encountered near Wirrabara. We wondered if we should continue or abandon our quest to find Dawson. As we passed the small cemetery, we could see it was not far to go so we decided to risk it. The remains of a solid hotel stand on the corner of the main intersection of what was once Dawson.

What happened next was one of those serendipitous moments when I felt that the spirits of my ancestors were watching over me as I researched my family history. In that deserted landscape, a farmer appeared driving his ute with his working dog beside him. He stopped to chat and was naturally curious about what we were doing in Dawson. I told him about my interest in Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church and to my amazement he told me that I would find the keys hanging on a hook in the small community hall nearby and I could return them there when I had finished looking inside the church.

When I entered the church, I was moved to see one of the stained glass windows had been dedicated by my great grandparents “Andrew and Mary Dempsey”. I have visited many of the great cathedrals of Europe, but they did not move me as much as this small church in the bush. I felt a sense of grief and loss for my ancestors who had built this church and after a few years had to leave it behind when they were forced to abandon farming in this inhospitable environment.

The last Mass was held in the Church in January 1970. More than 50 years since it was closed and 140 or so years since it was built, the Church building, its stained-glass windows and beautiful wood ceiling remain in good condition – a testament to the care with which it was constructed in 1885. The church’s architect was Father John Henry Norton.

John Henry Norton was born on the Ballarat goldfields in 1855. His father was English and his mother was Irish. As a young child he attended a Methodist Sunday School but later turned to his mother’s Catholicism. In 1870 he was received into the Church. Bishop Reynolds of the diocese of Adelaide sponsored his studies for the priesthood overseas. He was a student at St Kieran’s College, Kilkenny for two years and then a seminarian at the Propaganda College in Rome. He received his Doctorate of Divinity from the College and was ordained a priest on 8 April 1882. On his return to South Australia he was appointed to the parish of Petersburg, now Peterborough. Father Norton was responsible for designing several notable buildings in his parish. He was consecrated as Bishop of the then Port Augusta diocese at St Francis Cathedral, Adelaide on 9 December 1906. Bishop Norton had a close connection with the Dempsey family over many years. He officiated at the marriage of my great grandparents Andrew Felix Dempsey and Mary Ann Naughton at St Sebastian’s Church, Peterborough in 1884. He married my grandparents, Patrick Joseph Dempsey and Mary Lilian Howard at Our Lady of Dolours Church, Yongala in 1911. He also officiated at many Dempsey family baptisms and funerals. My mother did not leave behind many precious possessions, but there was one item which was very dear to her: a sepia-toned picture of the Sacred Heart in an oak frame which was a gift from Bishop Norton to my grandparents on their wedding day. My mother said in her memoir that the picture has a great deal of meaning for her and expressed the hope that some member of the family would take care of it when she was no longer able to do so.

Eventually my great grandfather Andrew Felix gave up trying to farm in the Hundred of Paratoo. His land was sold for less than the 10 per cent deposit paid on it. The Dempseys moved south and started anew, farming on land sub-divided on Old Canowie Station, between Whyte Yarcowie and Jamestown. Andrew Felix Dempsey purchased a property of 800 acres near Whyte Yarcowie for my grandfather. Grandpa was not given the land; he gradually repaid his father and by 1924 had succeeded in doing so.

My grandparents moved to this farm following their marriage in 1911. This is where my mother spent her childhood in great comfort and security. “It seemed to me, as a child, that the farm and home might well have been there for centuries. That’s how secure everything seemed to be.”

My grandfather had great devotion to Our Lady of Mount Carmel. His birthday coincided with her Feast Day and he named his farm near Whyte Yarcowie “Carmela” in her honour. He never forgot the church of his childhood. On the occasion of the closing of the church in January 1970, he wrote an article in the Witness, the monthly newspaper of the Port Pirie Diocese, expressing his sorrow. He recounted some amusing anecdotes about his days serving as an altar boy. He recalled that when he was a student at the Dawson Public School (the Catholic school had closed because of drought) the school had over 60 pupils on the roll book and “now there is no one living in the township of Dawson. What a mistake was made when the Government in defiance of the advice that Goyder gave them that they should not cut up for closer settlement any land outside Goyder’s line of rainfall. And now the lovely building is to be abandoned.” According to another correspondent in the Witness, Cardinal Norman Gilroy, during the time he spent as Bishop of Port Augusta 1935–1937, was reported as saying that the Dawson church was like a small Cathedral in a desert.

A year following the closure of the Church my grandfather died aged 84 at the Little Sisters of the Poor, Myrtle Bank, Adelaide.

Sources

1. ‘Bruce Swann: Australian realist landscape artist, 1925–1987’. Estate of Bruce Swan, https://www.bruceswann.com/landscapes.html

2. Data SA, ‘Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church’, SA Heritage Places Database Search, https://maps.sa.gov.au/heritagesearch/HeritageItem.aspx?p_heritageno=16010

3. Margaret M. Press, John Henry Norton: 1855–1923 Bishop of Railways, Wakefield Press, Kent Town, 1993.

4. Joseph Dempsey, A Tribute to our Pioneer Ancestors: The Dempsey family in South Australia, Walkerville, 18 November 1933.

5. Mary Imelda Dempsey, Carmela, a memoir, February–April 1995

6. Witness. Catholic Monthly Newspaper of the Port Pirie Diocese. Vol XVI, No. 1, Pt Pirie, January 1970, p. 4